It hadn’t occurred to me before (I don’t know why) how good homosexual writers are with relationships. I recently watched the film version of The Deep Blue Sea, a recent version of Terrance Rattigan’s play. I was very impressed with it and decided to watch something I’d recorded in 2011, an hour long documentary on Rattigan by Benedict Cumberbatch. It was in that interesting documentary that it was stated that Rattigan’s female characters, including, Hester Collier, played by Rachel Weisz in the film, were actually based on men, that at the time the plays were written the characters had to be changed because homosexuality was against the law.

It hadn’t occurred to me before (I don’t know why) how good homosexual writers are with relationships. I recently watched the film version of The Deep Blue Sea, a recent version of Terrance Rattigan’s play. I was very impressed with it and decided to watch something I’d recorded in 2011, an hour long documentary on Rattigan by Benedict Cumberbatch. It was in that interesting documentary that it was stated that Rattigan’s female characters, including, Hester Collier, played by Rachel Weisz in the film, were actually based on men, that at the time the plays were written the characters had to be changed because homosexuality was against the law.

I first came across a Rattigan play in the 1990s. I didn’t know or didn’t register who the play was written by. The play was Separate Tables, including Julie Christie and Alan Bates. The play was very moving. I remember my wife of the time saying ‘You could feel that’, and she was right – you could feel it. I recently watched the play again, but it is of course dated. With the best of intentions you can’t help noticing the hairstyles, the static camera – it’s still a great play but the shine is taken off it. The Deep Blue Sea was my first experience of Rattigan modernised – still set in 50s but with modern techniques. I felt it again. It is a very touching drama in which not much appears to happen.

This reminded me of The Browning Version, another moving Rattigan play. I suddenly realised that Rattigan gets right to the heart of the matter without making very much happen. I had watched an earlier version of The Deep Blue Sea. It was from 1994, televised as a play, but seemed even older. While the performances were good from the actors, including a young Colin Firth, it somehow remained quite static. Of course it was a play, not a film, but keeping the action in one dingy room somehow lessened its emotional impact, which was there waiting to be brought out. The main character, Hester, was also older, or looked it, which also (for me) reduced its effect. Subtle differences were introduced into the 2011 film: The action moved to a pub a couple of times; a musical scene in the pub showed the bond between Hester and Freddie Page (Tom Hiddlestone); Hester’s husband, Sir William Collier (Simon Russell Beale), was shown at dinner with his mother and provided more of a clue to the tension between husband and wife. The changes made for the film, just switching occasionally to the street, a pub, a telephone box, made the action more understandable and believable. The action in both was set in the 50s but the film had somehow made the action seem contemporary. It was very cleverly and sensitively done; I highly recommend the film to anyone who is interested. I have Rattigan’s plays and films in a BBC collection. Through no fault of their own they are dated, losing much of their impact.

The main thing I learned from the plays is that they are very emotional. Separate Tables moved me in 1983 and The Deep Blue Sea was incredibly poignant today; it left a lump in my throat, sent shivers down my spine and, believe me, it takes a lot to do that; I am a cynical person who dislikes ninety per cent of what I see, the pathetic excuses for drama we are now presented with. It takes a lot to affect me. The fact that Rattigan’s original intention in most of his plays was to have a man as the love interest rather than a woman does not lessen their impact, if anything it increases it.

The main thing I learned from the plays is that they are very emotional. Separate Tables moved me in 1983 and The Deep Blue Sea was incredibly poignant today; it left a lump in my throat, sent shivers down my spine and, believe me, it takes a lot to do that; I am a cynical person who dislikes ninety per cent of what I see, the pathetic excuses for drama we are now presented with. It takes a lot to affect me. The fact that Rattigan’s original intention in most of his plays was to have a man as the love interest rather than a woman does not lessen their impact, if anything it increases it.

Why do homosexual writers get right to the essence of relationships? Men are obsessed with sex and very few can write honestly about women. Women have other priorities, but again it is their own path they are interested in – there is a constant and never ending battle, rarely acknowledged. Homosexual men in general remain apart from the mating game. Whatever their heart desires, parenthood (until recently) was not a priority for gay writers. Although it is complicated, one could say that they are neutral, above the fray, and therefore write honestly. Cyril Connelly once said that:

‘The pram in the hallway is the enemy of art’

despite the valiant efforts of both men and women, this remains true. Men, no matter what they say, are only interested in sex. Women are interested in rather more. Homosexual men, freed from the battle of the sexes, are free to observe women as neutrals.

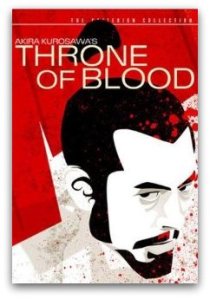

Tennessee Williams based his fragile women characters on men. Blanche, in A Streetcar Named Desire is based on a man. She is wise but broken by a cruel world; she is a mixture of toughness and vulnerability. A Streetcar Named Desire is another play that I find very emotive; I can watch it perhaps once a year, although, as usual, I prefer the film version. For me the tragedy of the play was the relationship between Blanche and Mitch; they were perfect for each other: Blanche’s wisdom would have smoothed Mitch’s rough edges, massaged his ego and Mitch would have provided much needed, last resort protection for Blanche. But Mitch’s ego, his twisted idea of morality led him to reject her and watch, albeit guiltily, as Blanche was taken away to the asylum. Real, heart rending tragedy. Williams once said that he just wished people would stop ‘being so beastly to each other’, which does rather seem to be a more typical female wish.

EM Forster’s Howards End is one of my favourite books. The main female characters appear full of reason and wisdom, while the men are merely insensitive, competitive and not very bright, apart from the tragic Leonard Bast. Forster did not make all his female characters wise, but his main protagonists were. Not openly gay, like Williams and Rattigan, Forster nevertheless wrote in a similar way: above the fray. Henry James, if we believe his many biographers, was celibate. Celibate or not, he was probably homosexual and wrote of women, incredibly long-windedly, but honestly. The film Wings Of The Dove demonstrates, briefly, his talent.

EM Forster’s Howards End is one of my favourite books. The main female characters appear full of reason and wisdom, while the men are merely insensitive, competitive and not very bright, apart from the tragic Leonard Bast. Forster did not make all his female characters wise, but his main protagonists were. Not openly gay, like Williams and Rattigan, Forster nevertheless wrote in a similar way: above the fray. Henry James, if we believe his many biographers, was celibate. Celibate or not, he was probably homosexual and wrote of women, incredibly long-windedly, but honestly. The film Wings Of The Dove demonstrates, briefly, his talent.

Of course, sensitive direction is essential and Terence Davies (The Deep Blue Sea), Elia Kazan (A Streetcar Named Desire), James Ivory (Howards End) and Iain Softley (Wings Of The Dove) all spotted the potential of the material and synthesised it wonderfully.

Lastly, in this necessarily brief reflection, comes Shakespeare. He was almost certainly bi-sexual. Of his 154 sonnets, 127 were written in praise or lust for an anonymous beautiful boy, only 25 to a mysterious dark haired woman. Shakespeare, many years before anybody else, wrote wonderful parts for women.

He was aware both of their qualities and faults and wrote about both. Generally though, I think he admired women over men. Anyway, I accept that this is a personal opinion and not many people will have seen the plays or films or know what I’m trying to explain. So, I defy anybody to watch the film versions of A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), Howards End (1992), Wings Of The Dove (1997) and, especially, The Deep Blue Sea (2011) and not be moved. All the films get right to the heart of relationships. I’d be interested to hear what you think.