I’ve always wanted to be a writer, sort of. Apparently my junior school teacher told my mother that my subject would be English. It wasn’t. It wasn’t anything. I was far too busy playing truant, misbehaving and generally having a good time. I took an interest in books in my late teens, but was still far too lazy and preoccupied to get seriously into literature. I loved foreign holidays because I’d take a dozen books with me and read them all. To me that was what holidays were for. At home I was too busy drinking, chasing girls, taking drugs and being bad, to read. I probably read as much during one holiday as I did during a whole year at home. I wanted to read; I bought loads of books – I loved them – I just didn’t read many of them.

.

Times have slowly changed. Now I read a lot, have done for many years, but I still allow myself to be distracted by TV and the Internet. I write a lot too. I have actually written all my life, jotting down ideas, starting short stories, even novels, but never really sustaining anything the way real writers do. Only age has made me slow down and write and I’ve become fairly good at it: one published memoir and a novel just submitted. But it took me forever to do it. The memoir was the result of ten years’ work, on-and-off; the novel has taken me a year, although it was roughly complete in a couple of months.

.

And when you come to write: How do you write? I must have read a hundred books on writing, but I’m not sure I’ve taken one bit of advice. I still sit down and write the way I always do, always have done, with some learning on the way that has been absorbed rather than learned. A sort of osmosis. And that osmosis, the absorption has come about through reading and thinking about what I’ve read, all the time; even in those lazy early days I realise that I was reading and writing and thinking and absorbing, watching people, thinking about it, storing it. And I love books. I love stories.

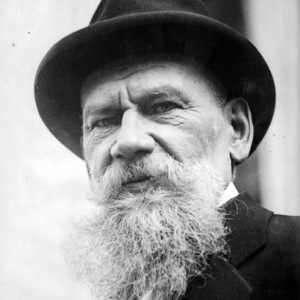

But how do you write? Can it be taught? I think the churning out of stories: vampire stories, love stories, detective stories and all the other variations can be taught, especially in the techno-age. I think real writers are born, not taught: Tolstoy, Balzac, Shakespeare, Steinbeck – they wrote because they couldn’t help it, and they don’t get forgotten. They are with us always. They told great stories.

.

In How I Became a Famous Novelist, Steve Hely wrote:

.

But as I walked out through the shelves, I looked at the work of my colleagues. There was Hemingway – A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls – all those pseudo-epic titles with women dying in the rain, bullfights, and Italian vistas. He knew the deal. He knew doomed Mediterranean romances would pay for Key West beach view and a new fishing boat. And Fitzgerald, who’d tricked the eye with an Ivy League pedigree and convinced the world that a rich guy who threw parties was some kind of metaphor. There was Faulkner, a southern huckster in the Bill Clinton mould, who suckered you in with his honey voice and tales of landscapes soaked in tragedy.

.

Is this true? The great novelist as con-artist? It made me think. I like Hemingway’s short stories. I loved The Old Man and the Sea when I was very young, but found it mostly awful when I returned to it recently. I didn’t like a Farewell to Arms; it read like the script to a very bad ‘B’ movie. I liked The Great Gatsby, but not that much. It’s OK, but I’ve never understood its reputation. I’ve never read Faulkner. Con-artists? Hely continues:

.

It went on back to Homer, who’d written stories so ridiculous, so full of special effects and monsters and busty, half-divine sluts that Hollywood would be ashamed to make them. And he’d pulled it off! He’s punched it up with rosy -fingered dawn and the sickeningly cloying scene of Prium begging for his son’s body. That blind old trickster probably got more chicks (or dudes) than Pericles.

.

On through Dickens, with his pleading orphans and sweetheart aunts; Mark Twain, with his little cherub-faced rascals and mock rural slang; James Joyce with his whisky-soaked-stage-Irish blarney – they were all con-artists. They weren’t any better than the guys who write beer commercials or sell car insurance over the phone. They just had a different angle.

.

Now, Dely is writing tongue-in-cheek here (I hope), but is there any truth in what he says? I’ve read very little Homer (I find it difficult), but I like Dickens and Mark Twain a lot. James Joyce’s early stories were great but then he lost me – I’ve tried Ulysses several times and it always defeats me. But no better than the guys who write commercials?

.

Norman Mailer wrote that

‘It’s as hard to learn to write as to play the piano’.

It is. Even for the jobbing writer who turns out average stuff. Sitting down in front of a blank page is a real challenge, it can be daunting, and it was just as hard for Joyce and Hemingway. Being a writer is not easy. Take this from someone who invents fresh avoidance tactics every day. I would do anything to avoid writing. Con-artists? I don’t think so. Lucky, in a few cases, maybe, shysters, no.

But back to how to write. For all the books I’ve read on writing, I think I’ve only picked up a few rules, and I probably knew them anyway. One of them is Elmore Leonard’s favourite rule: Do not use adverbs: ‘said’ with the name of the speaker at the end of a piece of dialogue is enough, and only occasionally to identify the speaker. If I pick up a book in a shop and read ‘John said hopefully’ or ‘sadly’ or ‘doubtfully’ or whatever, I put the book straight back on the shelf. The reader does not need to be told. They can and want to figure it out for themselves. If the writing is good enough the reader will know how the words are spoken or they will work out their own version. Don’t tell them.

.

Don’t tell the reader how your characters are feeling.

.

Chekhov this time:

.

Shun all descriptions of the characters’ spiritual state. You must try to have that state emerge from their actions. The artist must be only an impartial witness of his characters and what they said, not their judge.

.

Let your readers judge character and feeling. Let them do the work. That’s half the pleasure of reading. I remember when I wrote my memoir, describing a policeman (who had caused me a lot of trouble) skidding away from a police station on his motorbike, leaving me standing in a cloud of dust. A woman who later read the account said she liked the description. Why? Because you didn’t say how it made you feel.

.

Sis Field writes screenplays but his advice applies to any writer of fiction:

.

Without conflict there no drama. Without need there is no character. Without character there is no action. Action is character. What a person does is what he is, not what he says.

.

Action is not necessarily people fighting or shooting or special effects. It can be a knowing smile or the way someone smokes a cigarette. Elia Kazan, someone else who worked with the screen, said

.

‘It’s twenty times better if violence is suggested rather than if you’re explicit. What you imagine is much more frightening than what is seen.’

.

The same applies to writing novels. Take your reader into another world, tell them a story, but let them imagine the most important aspects of it.

Those are the only things I’ve picked up on from all those books on writing, and I think I knew them already. I absorbed what made good writing from the hundreds of good books I’ve read. And of course you need a modicum of talent. And the most important rule of all?

Work hard. Really hard. The aspect that I find the most difficult.

As G.K. Chesterton said, there is only one way:

Apply the seat of the pants to the chair and don’t get up until it’s finished.

.