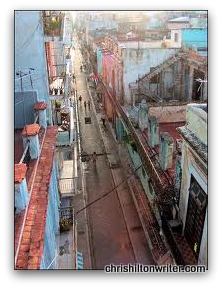

I didn’t really ask myself in the past – what do people do here? I still don’t know but I have much more idea. What almost everybody does is something. Starting at around five in the morning, a constant stream of people pass beneath my balcony; just one street of millions in the city. Among the first to arrive are the taxis, not taxis in the imagined sense, but ordinary low level private cars. They use the seventy yards or so just before the corner as a queuing spot for customers, perhaps eight or so taxis at any one time, constantly changing as customers take the first in the queue, all day, six or seven days a week. Although this happened before; there were always willing drivers to take people on whatever journey they wished, this is more official. I don’t know how much they charge because we only take bicycle taxis, of which there seem to be many more than were here a few years ago.

Whatever they charge, they are just part of the burgeoning private enterprise; along with the taxis are soft drink sellers, fruit sellers, cloth sellers, trinket sellers – anything sellers. All this activity takes place non-stop, every day, along with what must be the normal day-to-day activity of everyone else. The daily pushing of carts, trolleys, the carrying of goods, those who work and those who don’t – a constant stream of people – in one street, my street, one of many, many thousands.

There are more people begging on the streets, more selling Granma, the daily paper here, more persistently, more of a nuisance and mostly completely tolerated by hotel staff and anyone else involved. Perhaps that is the result of a more tolerant attitude to free enterprise. While they were once stopped or discouraged by police, they are now more ubiquitous. Nothing like as bad as in almost any other country, but certainly more here, more real and more confident.

The Capitol is closed for renovation, as is a very big shopping centre close by and many public buildings. No matter what else is happening here the country is gearing up for more tourism. The shopping centre contained six or seven floors above it, also closed and empty. What happened to the people who were in those rooms? I don’t know. Were they moved elsewhere? Will they be able to return? I don’t know.

It is hard to tell what is going on here. Most people take no interest, too busy in surviving, getting by. There are more paladares, more taxis, more stalls selling bits and pieces. I asked Yuri if life was easier now or more difficult than, say, 2006. She says things are easier. What of the buildings? Coming in from the airport there seems to be no difference in anything: people still stand by the road waiting for lifts or rare buses; people still seem to struggle with their daily lives. Our lift from the airport stopped along the way to carry out some private business or other. Old and central Havana, where I spend very much most of my time, is different. More people have more, though not so that most people would notice.

With the world economy in a complete mess, demonstrations and revolts occurring everywhere: Egypt, Spain, Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Greece… what are the Cubans doing? Yuri has not the slightest interest. At the moment I don’t know anyone that has, although if I make contact with more English speakers or find an interpreter then I’m sure there will be a different story. At the moment I don’t care. I am curious though. I know only what I see. Some of that I may interpret correctly, much I’m sure that I don’t.

The police have new cars. There are new buses although they are as full as ever and the queues remain long. There are designer stores, many more now than before, and not just for tourists. This is one of the big contradictions here: How can ordinary Cubans, on a wage of ten dollars a month, afford the prices, which are much the same as any other store worldwide. But many Cubans do afford the prices, perhaps with money from the United States or perhaps through employment in the more profitable parts of the tourist industry or perhaps through the new entrepreneurship, although I very much doubt it.

Everywhere you go is fantastically clean in Cuba. A woman comes every other day to clean our apartment. If it were left to me I would probably give it a very quick once over, maybe once a week. Just tidy the bathroom and the kitchen and a quick sweep elsewhere. She takes between two and three hours every time. Everything is spotless. You do come across the odd mosca (fly) and very occasionally a mosquito; otherwise I have never seen an insect in any Cuban house.

It is not just the cleaning lady who is so conscious of cleanliness. We have her because I rent a room, otherwise the lady of the house would clean everything every day. Many years ago, when I was with Yamilia, although she was basically lazy, she would always clean the house first thing. It is the same wherever I’ve stayed in Cuba – I’ve never seen a dirty house.

It seems to be part of the Cuban DNA. The floor is always covered with water and mopped – all rooms have tile floors. Of course there are many dilapidated buildings which, until they get attention, are left to rot, but any inhabited house, no matter how humble will be clean.

Certainly things have changed since I first came here. Cubans can now stay in their own hotels (if they can afford it), visit their own beaches. Accommodation is much easier to find. All sorts of jobs (about 180) have been added to an entrepreneurial list. In other ways it’s not so good. The bars on Obispo used to stay open all night, now they shut at twelve (so as not to disturb tourists in the few hotels nearby) – why come to Havana if you’re bothered by noise? Now, I don’t mind the changes, but a quiet Obispo does not seem right. Even though I rarely drink, I would like the choice; there are always other places, but it’s not quite the same.

Just now I don’t know. I know a lot and I will learn more, but after fifteen years there’s still loads I don’t know. Yuri knows everything, absolutely everything. I’ll have another go at Spanish (they talk so fast here), but I’ll try.