I took the photograph above in 2007 in a restaurant on Obispo, in Old Havana. The restaurant hadn’t been there when I lived in Havana from 2000 to 2002, nor was it on subsequent visits in later years; it had, like many buildings in Havana, been derelict and on the verge of collapse. Practical as ever, the Cubans merely helped the building to fall down, cleared a nice bright space, installed cooking facilities and a bar, put up a canopy for shade and in case of rain, provided music both live and recorded, and it became one of my favourite places.

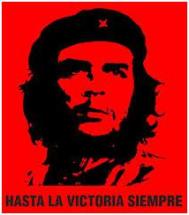

The mural of Che Guevara was painted by Osvaldo. It was about half complete when I first met him and took a few weeks to finish; he had also painted Ernest Hemingway. His payment for the work seemed to be that he was allowed to take a break every five minutes or so to hustle customers, including me. I was drinking alone one night and happy to buy him mojitos – instant friend.

The image of Che’s face is so ubiquitous that Osvaldo painted from memory; images of Che are everywhere in Cuba – they are also to be found throughout the world, but I’ll get to that later. I asked him if he was a painter. He dismissed the idea; the painting was nothing: he was a musician. Osvaldo was 40 but looked younger; he spoke good English and was impossibly lively, laughing and joking constantly as if he dared not stop. For the price of a few mojitos and the entrance fee to a club or two, I found places and people I otherwise wouldn’t have found. Osvaldo was contemptuous of his subject, Che Guevara, along with Castro, the revolution and the entire Cuban system,

“I am a musician, and what do I get for my talent? Nothing”

he told me, many, many times.

He was desperate to leave and chased a succession of female tourists in the hope of marrying one. He was just as tireless in this as in everything else: dancing (he was a fantastic dancer), joking, laughing, playing his music (he could play several instruments), singing and generally showing probably hundreds of women a good time. Sadly, when their holidays ended, his reward for this devotion to fun was,

He was desperate to leave and chased a succession of female tourists in the hope of marrying one. He was just as tireless in this as in everything else: dancing (he was a fantastic dancer), joking, laughing, playing his music (he could play several instruments), singing and generally showing probably hundreds of women a good time. Sadly, when their holidays ended, his reward for this devotion to fun was,

“Thanks for the great time Osvaldo, I’ll never forget you.”

and they left, without him. Osvaldo introduced me to the woman I’m still with today. When I returned later, I asked after Osvaldo

“He’s in Spain”, she said, “He married a tourist.”

I’m pleased for him and hope it’s what he hoped it would be, although I miss him. The restaurant had gone now too; the site remained but it was closed. I don’t know why.*

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara would have returned Osvaldo’s contempt, and disapproved of me also. While not humourless, and certainly possessing an unquenchable love of life, he was a very serious man:

“I do not cultivate the same interests as tourists”

he once said, putting me firmly in my place, although I do not think of myself as a ‘tourist’.

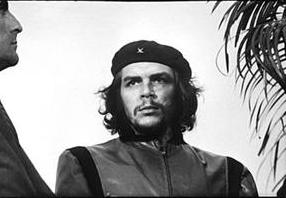

In April 1960, the freighter La Coubre exploded in Havana harbour while unloading munitions, killing at least 75 people and wounding hundreds. Guevara, a doctor, rushed to the scene to treat the wounded. At the memorial for the dead, a deeply affronted crowd were unusually quiet and reflective. Although it has never been proved who exactly was responsible for the explosion, the act was felt personally and viscerally as an attack on the Cuban people, on their efforts to free themselves from years of colonisation. Fidel Castro made a stirring four hour speech (quite brief for him) in which he used the phrase Patria o Muerte for the first time. While attention was focused on Castro, Che appeared briefly and gazed at the crowd for just for a few seconds. Alberto Korda, Castro’s official photographer, took two quick pictures of him before he disappeared again. It’s probable that Guevara knew of the photograph before he met his death in Bolivia, but, while it hung on Korda’s wall for seven years, few outside of Cuba knew of its existence. Soon after that the whole world knew of it.

Korda cropped his original image to show just the face. It hung in his apartment for 7 years.

Korda cropped his original image to show just the face. It hung in his apartment for 7 years.

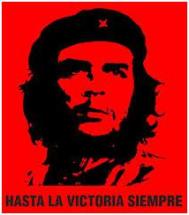

Much has been written elsewhere about Guevara, the copyright of the most reproduced photograph of all time, and the fortunes made from the reproduction and adaptation of Korda’s work. While Jim Fitzpatrick, who used the image to create his own stylised posters, signed over the copyright of his image to a Cuban hospital,

Much has been written elsewhere about Guevara, the copyright of the most reproduced photograph of all time, and the fortunes made from the reproduction and adaptation of Korda’s work. While Jim Fitzpatrick, who used the image to create his own stylised posters, signed over the copyright of his image to a Cuban hospital,

“because Cuba trains doctors and then sends them around the world.”

Andy Warhol insisted that profits from his own version of the image went only to Andy Warhol; he wasn’t alone. Korda, and his family since, have shown no interest in profiting from the picture. Che’s wife Aleida and his daughter are involved only in trying to limit the image’s misuse.

Korda’s black and white image has been cropped, adapted, stylised, coloured, digitally altered, used, abused and misused for nearly fifty years, but remains essentially the same: an expression of clear eyed determination to fight injustice that has inspired millions. It helps that the subject was charismatic, handsome and enormously attractive to women. Richard Gott, a journalist and writer who travelled to Cuba in 1963 to report on the revolution, met Guevara. In his book Cuba: A New History he wrote:

Korda’s black and white image has been cropped, adapted, stylised, coloured, digitally altered, used, abused and misused for nearly fifty years, but remains essentially the same: an expression of clear eyed determination to fight injustice that has inspired millions. It helps that the subject was charismatic, handsome and enormously attractive to women. Richard Gott, a journalist and writer who travelled to Cuba in 1963 to report on the revolution, met Guevara. In his book Cuba: A New History he wrote:

Guevara strode in at midnight, accompanied by a small number of friends, bodyguards and hangers on. He was impossibly beautiful. Before the era of the obsessive adulation accorded to musicians, he had the unmistakeable aura of a rock star. People stopped what they were doing and just stared. Like Helen of Troy, he had an allure that people would die for.

Unlike many who have been deified after dying young, Guevara was the real thing. He was painfully honest, courageous and completely dedicated. Sickly as a child in Argentina and asthmatic, he nevertheless enjoyed rolling around in the mud, and at the age of fourteen he progressed from mud to an affair with the housemaid. Friends who spied on him described his enthusiastic lovemaking interspersed with blasts from his inhaler, the same inhaler used during the heated battles of his later career as a revolutionary.

His first experiences of poverty came during a 5000 mile road trip through South America, with his friend Alberto Granado, in 1951. Witnessing the crushing poverty of the rural poor set him on a course from which he never wavered. He abandoned his career as a doctor and, via Guatemala and Mexico, joined the Castro brothers Fidel and Raul in the revolution that toppled Batista in Cuba. It may seem naive now, but he wanted to eradicate poverty and create a more just world; people believed in that possibility then. Che was an incurable idealist while Castro was more interested in politics and power, a Fidelista according to Enrique O’Varez, once a student friend of Castro but one of the first who later tried to kill him.

Fidel Castro said of Che that

“he embodies, in its purest and most selfless form, the internationalist spirit that marks the word of today. “

But Che’s unwavering dedication to truth was painful and irritating to many of his colleagues, including Fidel. His rigid honesty spilled over into his personal life when he refused his wife Aleida’s request to go shopping in their official car,

“No Aleida. You know the car belongs to the government, not to me. Take the bus like everyone else.”

Raul Castro said:

“If the day comes when Guevara realises that he did something dishonest in relation to the revolution, he would blow out his brains.”

According to Alex von Tunzelmann, in her book Red Heat, Guevara had,

“always put his principles, however impossible, before the fundamental urge to win, and keep winning. [His] integrity was the problem.”

Integrity and politics do not go hand in hand. Perhaps only half-jokingly, Fidel said to guests at a dinner party,

”I’m going to send him to Santa Domingo and see if Trujillo kills him.”

After a spell in charge of the National Bank of Cuba, where he nearly wrecked the already fragile economy, and disillusioned with realpolitik, he decided to take revolution elsewhere, disastrously to the African Congo and then to Bolivia. He wrote a farewell letter to the Cuban people and Fidel which included the line:

“If my final hour comes under distant skies, my last thoughts will be for this people and especially for you.”

Castro, while publicly expressing sadness at his departure, must have been glad to see him go.

Later, in Bolivia, he believed that the people would rise up as they had in Cuba, to bring down an oppressive government. Richard Gott wrote that

“He believed with passion that small groups of armed men could defeat established armies, as they had done in Cuba.”

He was wrong. The people were frightened and cowed, too afraid to act; many were willing to betray Guevara and his small band of followers. The end was inevitable. He was isolated with just 24 companions. His death came in a school room at the hands of a Bolivian soldier. Accounts vary, but it is certain that the Bolivians wanted him dead and to make it appear that he had died in battle. They also wanted his face untouched so that they could display him, in death, to the world. It seems certain that he did spit at his executioners and say;

“I know you’ve come to kill me. Shoot. Do it. Shoot me, you coward! You are only going to kill a man!”

A Cuban sniper, Felix Rodriguez, working for the CIA was also present. He claims that he gave the order to shoot Guevara and asked him if wanted to say anything to his family. Guevara replied:

“Tell my wife to remarry and try to be happy.”

In the last letter to his children he wrote:

”Your father has been a man who acted according to his beliefs and certainly has been faithful to his convictions. Until always, little children. I still hope to see you again.

A really big kiss and a hug from Papa.”

There is no doubting his bravery and ability when he had loyal followers, demonstrated when he won a great victory at Santa Clara against all odds. The battle was accurately portrayed in Steven Soderbergh’s epic film, Che. Over 50000 Americans stood, heads bowed, in front of the Lincoln memorial on the news of his death, while ironically it went almost unnoticed in Moscow where disdain was expressed for his adventurism. In the White House, the news was received with satisfaction. Walt Rostow, advisor to President Kennedy, said, “They finally got the son of a bitch. The last of the romantic guerrillas.”

There is no doubting his bravery and ability when he had loyal followers, demonstrated when he won a great victory at Santa Clara against all odds. The battle was accurately portrayed in Steven Soderbergh’s epic film, Che. Over 50000 Americans stood, heads bowed, in front of the Lincoln memorial on the news of his death, while ironically it went almost unnoticed in Moscow where disdain was expressed for his adventurism. In the White House, the news was received with satisfaction. Walt Rostow, advisor to President Kennedy, said, “They finally got the son of a bitch. The last of the romantic guerrillas.”

So much has been written about Guevara that would not have been written without the existence of Korda’s photograph. He has become a symbol of revolt, of hope in an increasingly homogenised world, where half the people live dangerous, poverty stricken and fearful lives while most of the other half don’t care or avert their eyes. For a multitude of reasons Cuba’s revolution failed, although it tried, and remains a symbol of hope to many. Cuba can with justification be criticised; Che, through dying young, remains pure; his image portrays the man: his beliefs, his honesty, his courage and his humanity. Whatever happens to Cuba, however history judges Castro (and that argument will never end), that image and its power to inspire will endure. He became worth more dead than alive; not only to Fidel but to radical politics.

That it didn’t inspire Osvaldo is understandable. He wanted a better life. I hope he found it. I’ve seen that image of Che a thousand times and appreciate its power, but I prefer the man behind the legend: the man who set off with his friend to explore South America, who was inspired to action by the poverty he witnessed; the young man determined to have a good time, who fell in and out of love; the man who in battle cared nothing for cleanliness and wagered his compañeros that his shorts would stand up independently if he removed them – they did – and he won his bet; the young man who said after his South American trip,

“I began to realize then that there were things as important as being a famous researcher or as important as making a substantial contribution to medicine: to aid those people”

and never wavered from that promise; the man, who facing death, spat at his executioners and called them cowards. Irritating and unrealistic he may have been, but the image speaks of someone willing to strive for ‘impossible’ principles. Where many revolutionaries have proved to be frauds, fame seekers and sociopaths, Guevara was absolutely genuine.

I told Osvaldo the story of Che’s shorts. He didn’t stop laughing for ten minutes. I think Osvaldo would have liked that young man too, but times have changed. Richard Gott met Guevara just once. Strangely, he was present four years later in the aftermath of his death and, with a Cuban-American CIA agent, Eduardo Gonzalez, was one of only two people present who had seen Che Guevara alive and could identify the body. When Gott asked him where he came from, he replied

“From nowhere.”

Exactly.

“I have lived magnificent days.”

* The restaurant has since reopened. It’s still great, but in a different way. Osvaldo’s murals have gone.